John Keats stayed at Keats Cottage (known at the time as Eglantine Cottage) in July and August 1819, with his friends James Rice and Charles Armitage Brown.

The Keats Connection

Charles Brown took a summer holiday each year, and sub-let his part of Wentworth Place (now Keats House) in Hampstead. Hence, his lodger Keats must find alternative accommodation for the period, despite being low on funds. During the summer of 1819, Keats agreed to join his friend James Rice in Shanklin on the Isle of Wight. Charles Brown joined the pair later.

It has to be said that Keats wasn't overly happy while at Eglantine Cottage, but he did get a lot of writing done, which is no bad thing. He wrote a substantial portion of the play Otho the Great, the story of which Charles Brown (as co-author) was sketching out for him. Keats also started writing one of his most well-known narrative poems, 'Lamia'.

A great part of Keats' unhappiness was caused by his love for Fanny Brawne, whom he longed for desperately - but whom he could not afford to marry. He was considering alternative careers at this time, that might pay better than poetry, but such compromises were not to be, especially as his health was already worsening. His poetic vocation, his love for Fanny, his poor health, and his perennial need for enough money to live on (let alone marry on) were conflicting burdens that tore him every which way.

Then, as now, the old village in Shanklin and its Chine were a great tourist spot, and so the summer crowds did not help Keats' mood nor his ability to concentrate on writing.

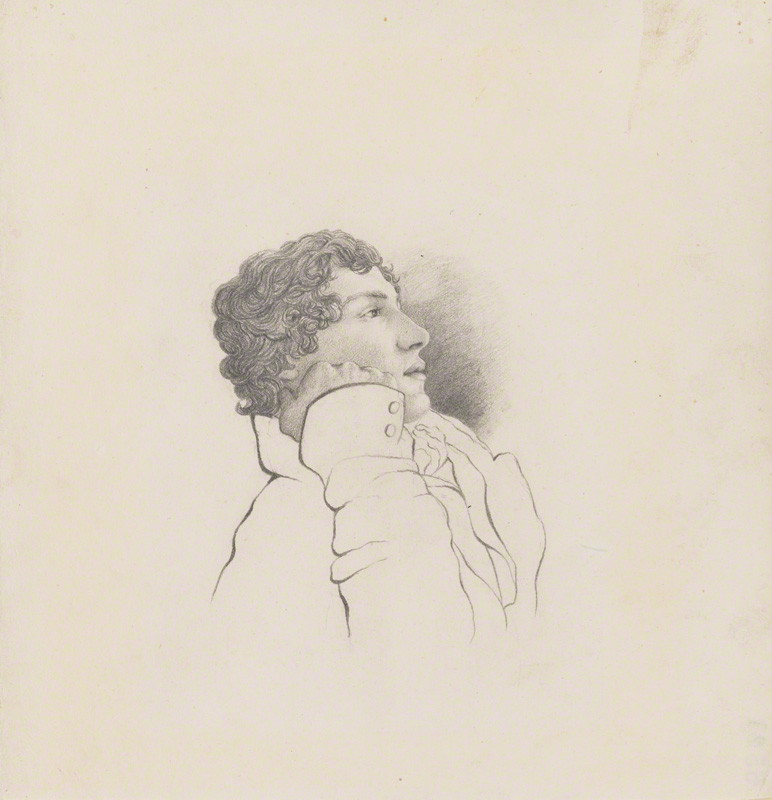

A happier association with Eglantine Cottage is that Charles Brown drew my favourite image of Keats while staying there, in July 1819. (Follow the link to see a copy downloaded from the National Portrait Gallery under their Creative Commons licence.)

In Between

The artist George Morland also stayed at Eglantine Cottage, in 1789. His Coast Scene with Smugglers (1790), for example, shows a view of Shanklin beach. (Links: George Morland page on Wikipedia; Coast Scene with Smugglers page at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.)

Other visitors to the Cottage apparently included the playwright Thomas Morton. (Link: Thomas Morton page on Wikipedia.)

I don't have much information about Eglantine Cottage over the years, but it was open to the public as 'Keats Cottage Hotel' before the current owners, David and Ewa, took over. It has since been refurbished, with respect for yesterday's visitors and consideration for today's.

Today

Mr B and I have stayed at Keats Cottage twice now, and we have really loved it. David and Ewa are very obliging and friendly hosts, and Ewa's cooking makes breakfast and dinner at the restaurant a real treat.

NB: The rooms are all up various flights of stairs, so people with mobility restrictions may need to plan accordingly. Part of the restaurant is at street level, however, so that is probably doable for all.

NB: There is no on-site parking, but there is a council car park just down the road, and the island-wide rate for a number of days' parking is quite reasonable.

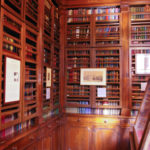

We have stayed in the Byron, Keats, and Shelley rooms on the first floor - and while I must say the Shelley room has the edge in terms of a superbly large bathroom, it is a real thrill to stay in the Keats room, which is where he stayed in 1819, complete with a view up to the Shanklin Theatre. I stayed on my own for two nights in that room, and wrote some of my novel The 'True Love' Solution there. What Keats would make of that, other than politely offering general encouragement, I have no idea!

David and Ewa host regular events at the restaurant, with focuses on various cuisines (Polish, Italian) or particular types of food or drink (wine, crab, vegetables).

I really can highly recommend the experience to all Keatsians!

Details

- Address: Keats Cottage, 76 High Street, Shanklin, Isle of Wight, PO37 6NJ

- Train: Shanklin on the Island Line

- Opening hours: The B&B is open throughout most of the year, but do check availability before you make travel plans. The restaurant is open five nights a week during the busy season, but fewer nights per week over winter.

Links

- Keats Cottage official site

- Keats Cottage official page on Facebook

- Keats Cottage official account on Twitter

- Shanklin page on Wikipedia

Nearby

- The top of Shanklin Chine can be found in the old village, just below where High Street becomes Church Road. It leads down quite steeply to Shanklin beach. Keats called the Chine 'wondrous'. (Links: Shanklin Chine page on Wikipedia.)

- Keats and his friends apparently had an outing to sketch St Blasius Church one day, before returning to Eglantine Cottage where Brown sketched Keats in the portrait I've linked to above. The church dates back to medieval times, but was largely rebuilt in 1859, so it would have appeared quite different to Keats in 1819. (Links: St Blasius Church, Shanklin page on Wikipedia.)