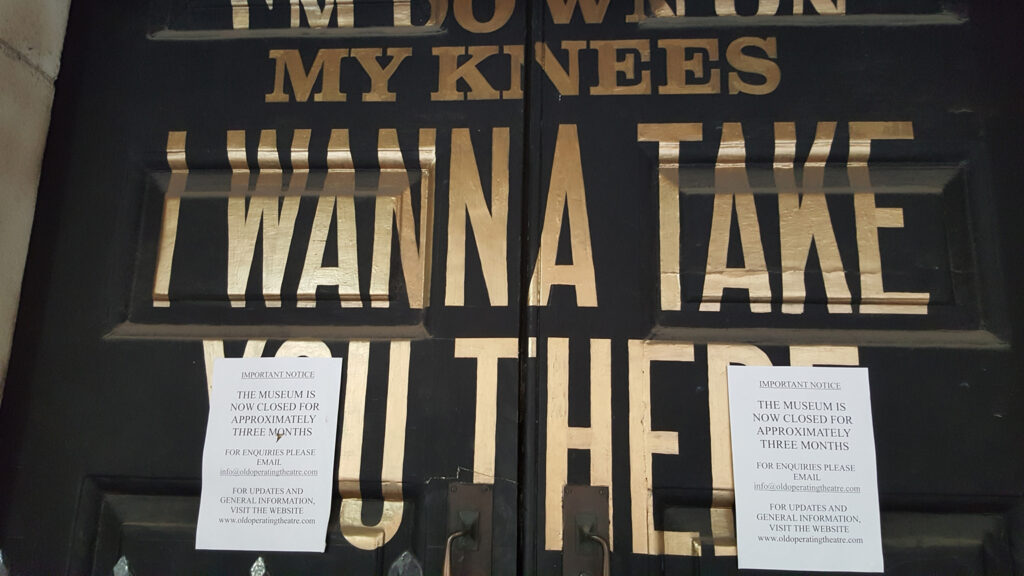

Outside the Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret. Not sure why, but the main doors feature Madonna lyrics painted in gold!

Outside the Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret. I think Keats would have been astonished by the Shard!

The Guy’s Hospital courtyard during renovations.

The Keats statue at Guy’s Hospital.

The Keats statue at Guy’s Hospital.

Guy’s Hospital.

Stainer (formerly Dean) Street, Southwark.

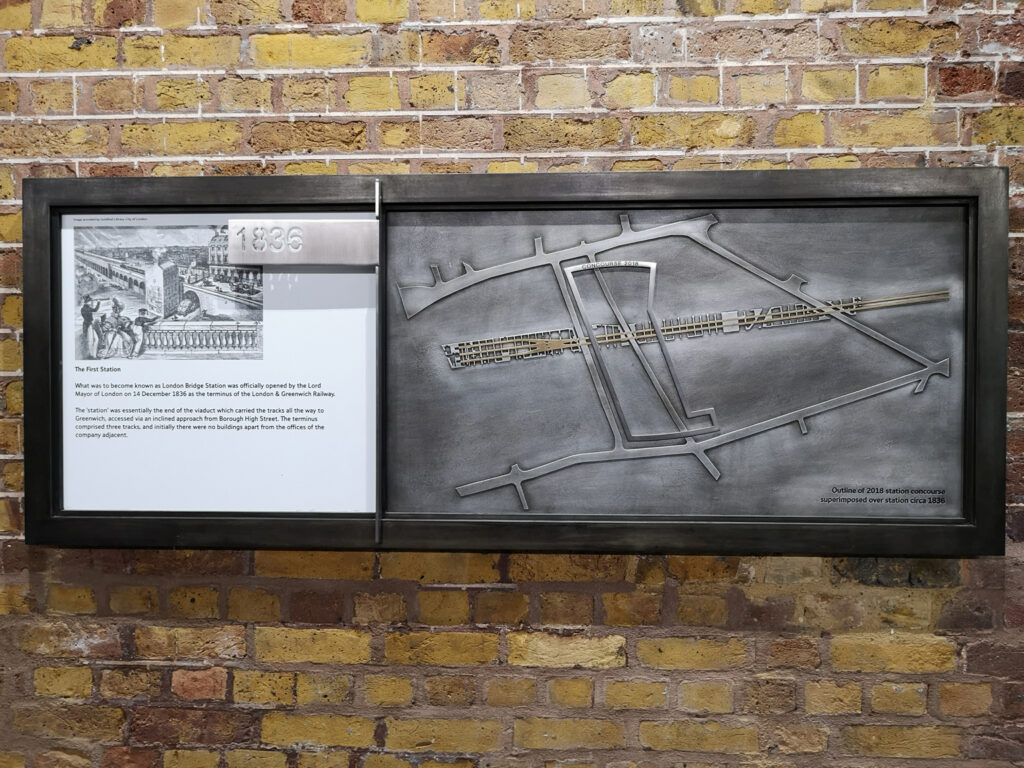

Stainer (formerly Dean) Street, Southwark. Display showing the location of the first railway lines in 1836. Dean St runs up along the left of the new station concourse.

Stainer (formerly Dean) Street, Southwark, looking towards Tooley Street.

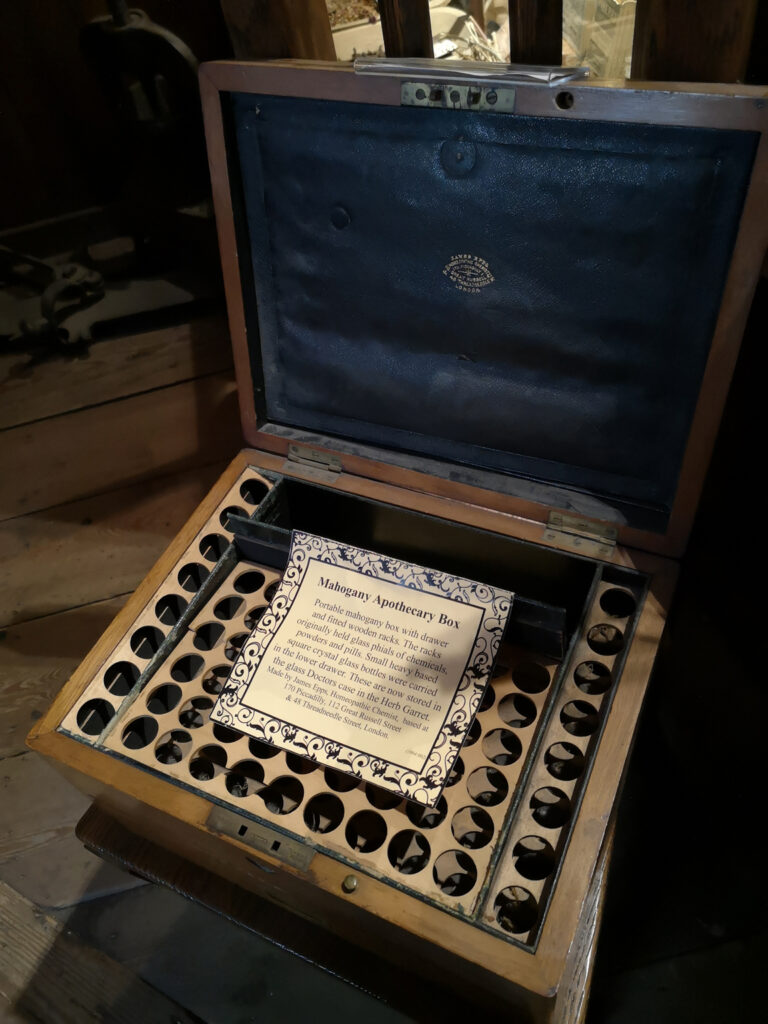

The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret.

The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret.

The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret.

The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret.

The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret.

The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret.

The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret.

The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret.

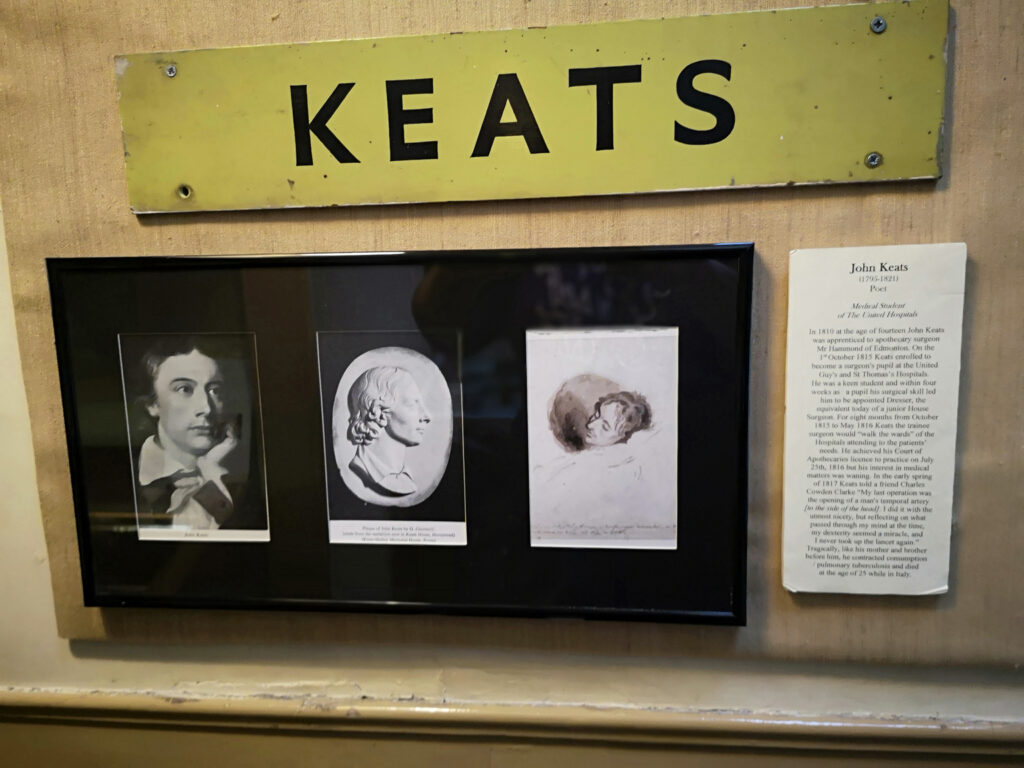

The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret. Display on Keats.

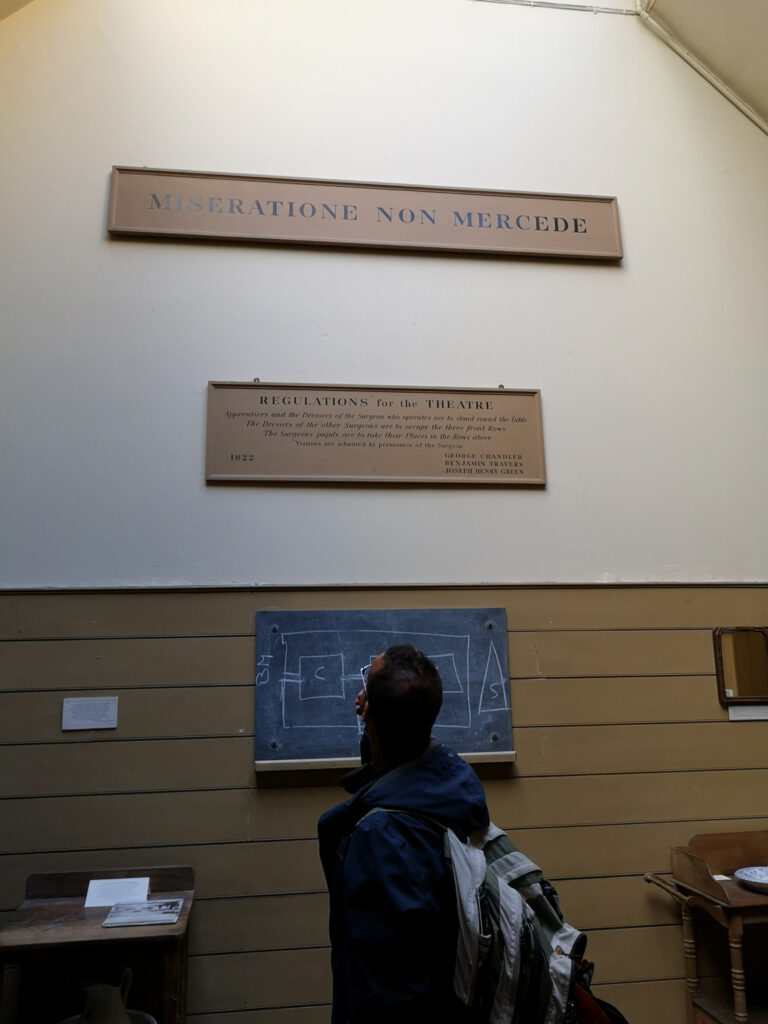

The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret. “Miseratione non Mercede” means “For compassion not for gain”.

The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret. It’s easy to imagine Keats here when looking at such old timbers.

8 Dean Street, Southwark, London

John Keats wrote his first significant poem while lodging at 8 Dean Street, Southwark.

The Keats Connection

Keats moved to lodgings at 8 Dean Street in late September 1816, on returning from a holiday in Margate with his youngest brother Tom. Keats was returning to London in order to take up his studies at nearby Guy’s Hospital.

Keats lived at the Dean St lodgings on his own, though the original plan had been for Tom to live there with him. Instead, Tom went to live with the middle brother George.

On 9 October 1816 Keats wrote to his friend Charles Cowden Clarke, giving Clarke directions to visit him. Keats wrote:

Although the Borough is a beastly place in dirt, turnings and windings; yet No 8 Dean Street is not difficult to find; and if you would run the gauntlet over London Bridge, take the first turning to the left and then the first to the right and moreover knock at my door which is nearly opposite a Meeting.

(The “Borough” is the Borough of Southwark, and the “Meeting” would have been a meeting house for Quakers.)

Importantly, Keats wrote his first significant sonnet – “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer” – at Dean St, having returned there early one morning after a long night of literary discussions with Clarke. I haven’t found an exact date for him writing the poem, but it was definitely in October, at Dean St.

Keats didn’t stay long at Dean Street; by mid-November 1816, he was living at 76 Cheapside, London with his brothers George and Tom.

In Between

Dean Street was later renamed Stainer Street, apparently in honour of Sir John Stainer (1840-1901), a composer and organist who was born in Southwark. (See the Street names of Southwark page on Wikipedia.)

On 17 February 1941, during the Second World War, a bomb fell on a railway arch over Stainer St, killing 68 and injuring 175 people who were sheltering there. There is now a blue plaque in their honour.

At some point, as the London Bridge railway station grew, the buildings where Keats lodged were demolished. Eventually, Stainer Street was blocked off and no longer accessible to the public. There are now no buildings other than sturdy brick arches between Tooley St and St Thomas St, supporting the many train tracks coming into London.

Today

Stainer Street was reopened in October 2018 as part of the new London Bridge station concourse, for pedestrian access only. There is nothing (yet?) acknowledging the connection with Keats.

There is a large, beautiful artwork on the arched ceiling towards the Tooley Street end of the concourse, called “Me. Here. Now.” by Mark Titchner, installed in 2018. The main photo above shows one of the pieces, in which the message reads, “Only the first step is difficult.” Intentionally or not, I feel this is delightfully appropriate for the Keats connection.

It seems that No 8 Dean Street was about halfway along Stainer Street, on the eastern side (i.e. towards the National Rail station and away from the Tube station). (See below for the reference.)

Confusions

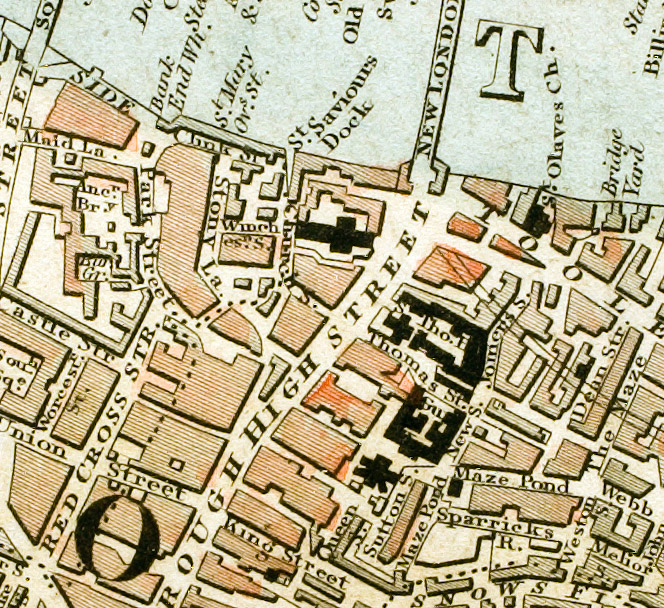

The Tooley Street page on Wikipedia suggests that Keats’ Dean Street equates to the northern end of Weston Street, which “connected with Tooley Street opposite Hay’s Galleria”. However, the Schmollinger map clearly shows Dean Street running parallel to The Maze, on the west, and Weston Street running directly into The Maze.

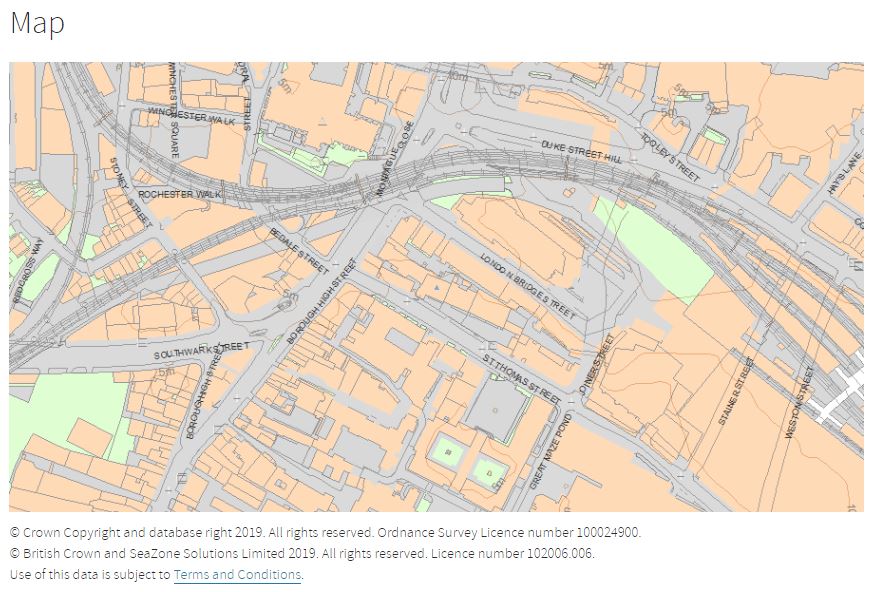

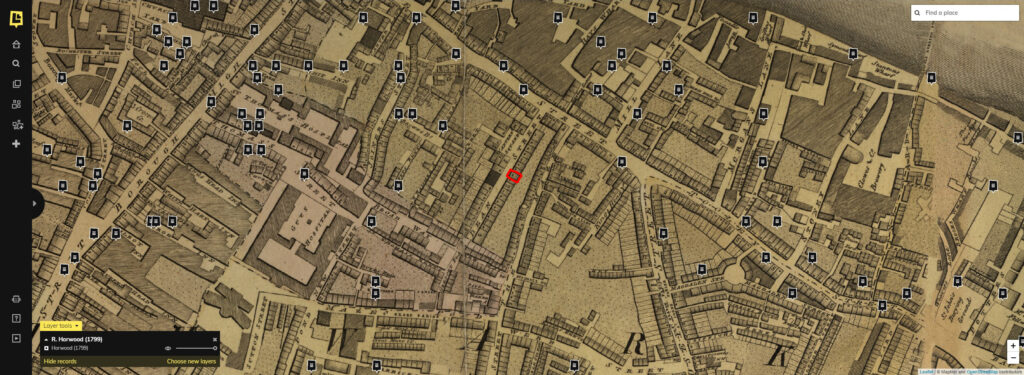

Meanwhile, the map associated with the 9A, St Thomas Street heritage listing on Historic England (copied below) shows Stainer Street to the west of Weston Street (with no mention of The Maze). It seems clear to me that The Maze and Weston Street are connected, and that Stainer Street is what Keats would have known as Dean Street.

This is further supported by this map on the Mapping Keats’s Progress site, which also indicates that No 8 Dean Street was about halfway between Tooley and St Thomas Streets. (Unfortunately this site states incorrectly that George and Tom lived with John at this address, but it can be difficult not to let errors of assumption sneak in!)

I should add that I was first alerted to the Dean St / Stainer St connection by a Network Rail employee, who was looking for information about Keats in anticipation of the opening of the new concourse.

However, any further information would always be welcome!

Updates!

I have since discovered the marvellous Layers of London website, which conclusively shows the location of 8 Dean Street, and the fact that it is now Stainer Street. The following images are taken using the 1799 map by Richard Horwood.

Details

- Address: Stainer Street, running between Tooley Street and St Thomas Street, London SE1

- Tube: London Bridge on the Jubilee and Northern lines

- London Bridge on National Rail

- Opening hours: the Stainer Street walkway is accessible 24/7, while the station concourse closes in the small hours each night while the trains aren’t running

Links

- London Bridge official site on Network Rail website

- London Bridge station map showing Stainer Street, on Network Rail website

- Re-activating Stainer Street article including mention of Keats, on ThamesLink Programme site

- Guy’s Hospital page including the Schmollinger map, on Wikipedia

- On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer page on Wikipedia

- Keats’ letter to Charles Cowden Clarke, 9 October 1816

Nearby

- Other Keats Locations nearby include Guy’s Hospital, The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret, and 8 St Thomas Street.

Guy’s Hospital, Southwark, London

John Keats studied medicine at Guy’s Hospital and qualified as an apothecary.

The Keats Connection

Keats completed his medical apprenticeship with Thomas Hammond, a doctor in Edmonton, in mid 1815. He then began studying as an apothecary-surgeon at Guy’s Hospital in Southwark, London. Guy’s Hospital was (and still is) a teaching hospital, associated with St Thomas’ Hospital.

Keats registered at Guy’s as a surgical student on 1 October 1815, and began working and studying there on 15 October. He qualified as an apothecary, but ended up deciding to quit medicine in late 1816, without becoming eligible to qualify as a surgeon.

Today

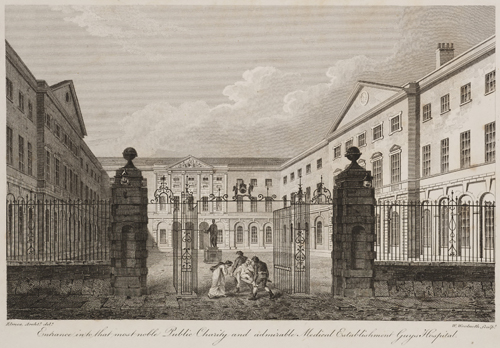

The courtyard entrance to Guy’s Hospital would still look very familiar to Keats, especially now it is pedestrian only (it used to be a car park).

If you walk across the courtyard and through the further colonnade, you’ll find two more squares opening up to either side. On the left, there is a statue of Keats himself, by Stuart Williamson, installed in 2007. I have sat there in the little shelter a few times, in search of peace.

Details

- Address: St Thomas Street, London SE1

- Tube: London Bridge on the Jubilee and Northern lines

- Opening hours: You can visit the statue during daylight hours. However, please be respectful of the hospital’s staff and patients!

Links

Nearby

- Keats lodged nearby at 8 St. Thomas Street and at 8 Dean Street

- Keats wouldn’t have known The Old Operating Theatre, but it would have been familiar to him, and he might have known the herb garret

The Old Operating Theatre and Herb Garret, Southwark, London

The Old Operating Theatre and the Herb Garret were part of St Thomas’ Hospital, which was associated with Guy’s Hospital where John Keats studied medicine. While the operating theatre was built the year after he died, Keats would have found it familiar, and he may have known the herb garret.

The Keats Connection

Keats studied medicine at Guy’s Hospital, Southwark, from 1815 to 1816. The students of Guy’s Hospital and St Thomas’ Hospital were entitled to observe operations conducted at either hospital.

Prior to this particular operating theatre being built, surgical operations on women patients would have been conducted at one end of the Dorcas ward – a situation understandably distressing for the other patients, especially with a crowd of students all jostling for position, not to mention the fact that this was in the days before the use of anaesthetic. In 1821, it was decided to create a separate, purpose-built operating theatre nearby.

The operating theatre we can visit today was built in 1822 in the attic of St Thomas’ Church. While this may seem an odd location, the space was at the same level as the Dorcas ward, and was already used as a “herb garret”. We assume this means that the attic was used by the hospital’s apothecary to store and work with medicinal herbs.

The building containing the wards directly abutted the church, so patients could be conveyed through a set of double doors at the end of the Dorcas ward, into a vestibule, and from there into the operating theatre.

Keats qualified as an apothecary, but not as a surgeon. He quit medicine towards the end of 1816, and later died in February 1821, so he wouldn’t have known this particular operating theatre. However, it wouldn’t have been unfamiliar to him – at least in function, if not exactly in form – and there is a chance that he at least knew of the herb garret and perhaps even had cause to use it.

In Between

The Charing Cross Railway Company bought the hospital’s land, and in 1862 the hospital began to move to its current location in Lambeth. The operating theatre was closed.

I am not entirely sure of the chronology here, but the double doors leading from the Dorcas ward were bricked up. At some point, the internal structures of the operating theatre were stripped out. Also, some of the floorboards were disturbed in the early 1900s when electrical work was carried out relating to the ceiling of the church below.

Although the operating theatre and garret weren’t entirely forgotten, they weren’t physically rediscovered again until 1956, almost a hundred years since they were last used. Raymond Russell was researching the hospital’s history, and decided to investigate the space – which at the time was only accessible by climbing a ladder up to the only remaining “entrance” high on a wall.

Russell found the shell of the operating theatre still existed, along with the plaster work and the flooring. While the structures such as the standings had been removed, the place hadn’t been further cleaned out, so there were still plenty of clues showing what had been built where.

No other 19th century operating theatre in Europe has survived, so this location is unique.

The operating theatre was reconstructed with some confidence, given the clues left behind. The operating theatre and the herb garret were then opened as a medical museum in October 1962.

Today

The museum can be visited seven days a week. It contains all kinds of exhibits relating to the work of apothecaries and surgeons in Keats’ time. There is a small wall display about Keats, with images of him, giving a brief outline of his association with the hospitals.

Two Warnings

First: Some of the surgical exhibits are not for the faint of heart! I am a tad squeamish, so I was rather nervous about this. However, I’ve visited twice now and found it easy enough to quickly glance past the worst of it – and there’s plenty of other things of great interest to make a visit worthwhile.

Second: Access is via a very narrow, steep, winding staircase in the church’s bell tower. There are 52 steps, so it’s a bit of a climb, and the only handrail is the thick rope running down the centre. I’m afraid there is no other way up to the attic if you are not in a position to be able to manage this under your own power.

Details

- Address: 9a St Thomas Street, Southwark, London SE1 9RY

- Tube: London Bridge on the Northern and Jubilee lines.

- Opening hours: Mondays from 2pm to 5pm

- Tuesdays to Sundays from 10:30am to 5pm

Links

- The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret official site

- The Old Operating Theatre official page on Facebook

- The Old Operating Theatre official account on Twitter

- The Old Operating Theatre page on Wikipedia

- St Thomas’ Church, Southwark page on Wikipedia

Nearby

- Keats’ lodgings at 8 St Thomas Street, London are literally just over the road from the museum and church.

- Also nearby are his lodgings (now destroyed) at 8 Dean Street, and of course Guy’s Hospital.

Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire

Keats and his friend Bailey visited The Birthplace and Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon.

The Keats Connection

Keats was staying with his friend Benjamin Bailey, in Bailey’s rooms near Magdalen College in Oxford. Towards the end of their month together, “they decided to pay homage to the presiding genius of their friendship”. (Keats, Andrew Motion, p193)

On 3 October 1817, they caught a coach to Stratford-upon-Avon, and visited Shakespeare’s birthplace (the house on Henley Street) and resting place (Holy Trinity Church), before returning to Oxford.

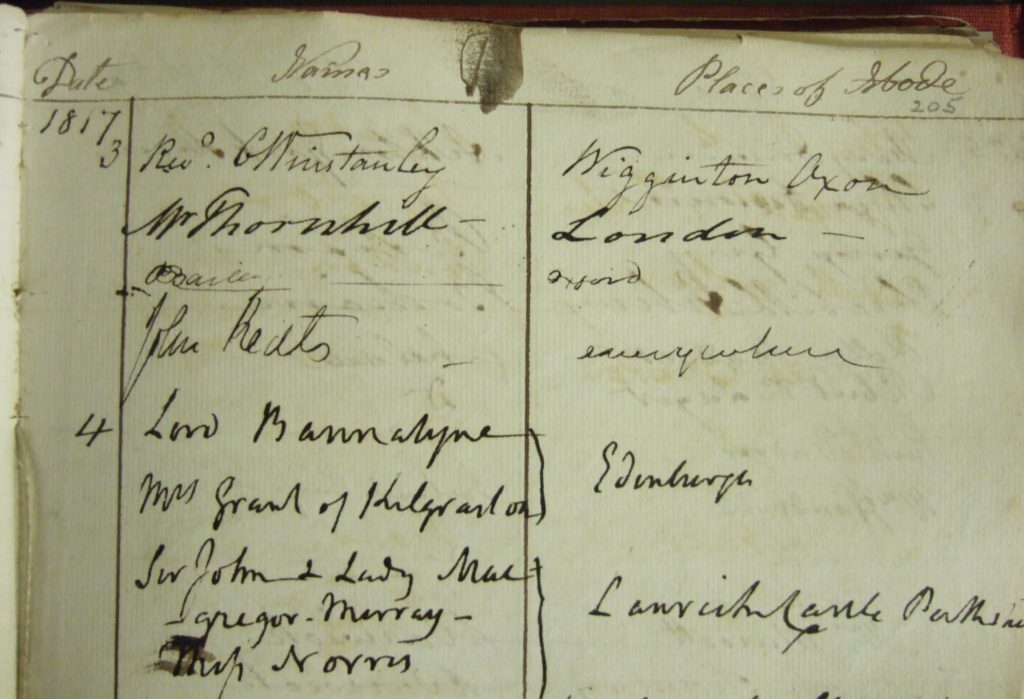

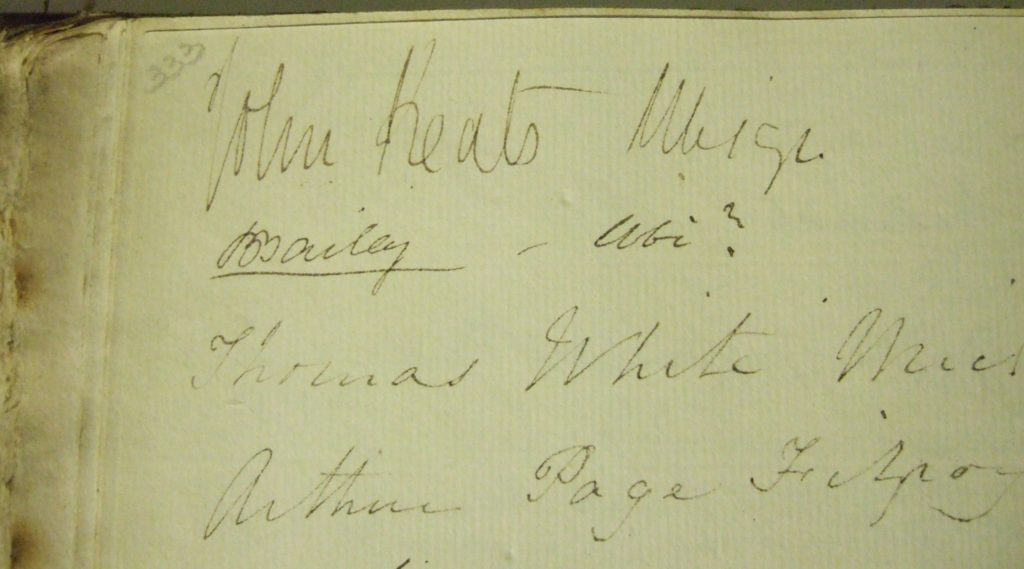

They signed the visitor books in both locations – though Bailey later indicates that they (also?) signed the bedroom wall in The Birthplace. If so, they were not the only ones! There was a grand tradition of signing either the walls or the panes of glass in the window. The much scratched window was eventually replaced, but is currently on display (protected behind glass!) in the house.

Bailey gives his ‘Place of Abode’ as ‘Oxford’, while Keats – mischievously? seriously? in a state of negative capability? – gives his as ‘everywhere’.

- Source of this image: bloggingshakespeare.com.

At the Holy Trinity Church, Keats provides the same place of abode – but in Latin this time: ‘Ubique’. Bailey then follows with ‘Ubi’, which I believe means ‘when, where’ in Latin – perhaps adding a question mark…? I am not learned in interpreting such things. But bless their hearts!

- Source of this image: collections.shakespeare.org.uk

Today

We can easily follow Keats and Bailey on their pilgrimage. The Birthplace and other significant Shakespearean locations are managed by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust and open to the public. The Holy Trinity Church is also open to the public, except on Sunday mornings and during any other services.

I assume, if you have the chutzpah or scholarly credentials, you could also ask to see the original visitors books in the archives.

Details

- Address: Shakespeare’s Birthplace, Henley St, Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire CV37 6QW

- Opening hours: nine to five, seven days a week

- Address: Holy Trinity Church, Old Town, Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, CV37 6BG

- Opening hours: nine to five-ish, six days a week

- afternoons only on Sundays

Links

- Shakespeare’s Birthplace page on the official Shakespeare Birthplace Trust website

- Holy Trinity Church official website

- Stratford-upon-Avon page on Wikipedia

- Shakespeare’s Birthplace page on Wikipedia

- Church of the Holy Trinity, Stratford-upon-Avon page on Wikipedia

Clarke’s Academy, Enfield, London

Keats and his brothers attended Clarke’s Academy in Enfield as boarders.

The Keats Connection

This school in Enfield was run by headmaster John Clarke, and his son Charles Cowden Clarke (who was a particular friend of and mentor to Keats). Keats’ uncle Midgley Jennings had attended the school, so there was already a family connection. There was, presumably, also the desire that the boys were educated in this liberal, even progressive establishment rather than the more traditional Harrow.

John and George Keats were enrolled in Clarke’s Academy in summer 1803, when Keats was seven years old, having both already attended a dame school. They continued at Clarke’s until the summer of 1810, when Keats was apprenticed to Thomas Hammond in Edmonton, and George began work in London.

The village of Enfield was at that time separate from London, and sounds quite idyllically rural and well-to-do. Keats’ grandparents lived in nearby Ponders End, though his grandmother Alice Jennings later moved to Edmonton (two miles from Enfield) when his grandfather John died in 1805.

“The school occupied a handsome three-storey building of dark red brick. It had been constructed … in 1672, and decorated with pedimented gables and a pillared facade ‘wrought by means of moulds into rich designs of flowers and pomegranates, with heads of cherubim over two niches in the centre of the building’.” (Keats, Andrew Motion, p23)

More importantly for Keats, there was a large garden stretching back behind the house. The image of this schoolboy reading The Faerie Queene in a “rustic arbour” at the edge of the garden near the woods, is just too sublime for words.

In Between

When the railway finally reached Enfield in 1849, the tracks were laid down through that long garden, and ended at the house, which became the train station.

The house was later demolished in 1872, and replaced by a new station (which in turn was demolished and replaced). The ornate facade of the original house was saved, however, and purchased (for £50!) for the Structural Collection of the Science Museum, then part of the South Kensington Museum. This is now part of the Victoria and Albert Museum; the V&A website currently lists the facade as being in storage.

Today

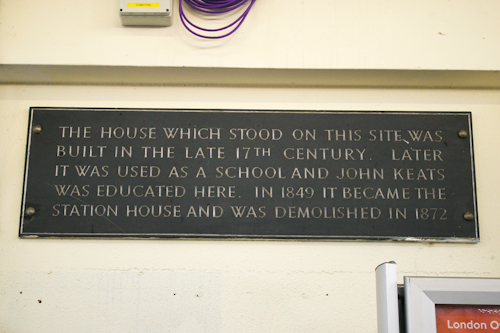

A modern train station (dating to the 1960s) now stands on the site of the house and former school, with a plaque acknowledging the connection to Keats. This station is still the end of the line, so at least you can sense the location and orientation of the original house and garden! The only thing here is to see, however, is the plaque opposite the ticket office.

The plaque reads:

The house which stood on this site was built in the late 17th century. Later it was used as a school and John Keats was educated here. In 1849 it became the station house and was demolished in 1872

Details

- Address: Enfield Town rail station, Southbury Road, Enfield, London EN1 1YX

- Tube: Enfield Town on the London Overground

- Opening hours: early until late, seven days a week

Links

- Architectural facade page on the Victoria and Albert Museum website

- Enfield Town page on Wikipedia

- Enfield Town railway station page on Wikipedia

- Charles Cowden Clarke page on Wikipedia

gallery | Edmonton

Church Street, Edmonton, London

John Keats and his siblings lived with their grandmother on Church Street in Edmonton, and Keats later worked as an apprentice at Thomas Hammond’s surgery on Church Street.

The Keats Connection

Alice Jennings

Keats’ grandmother Alice Jennings had moved from Ponders End to Church Street in Edmonton after his grandfather John Jennings died in early 1805. When Keats’ mother Frances Rawlings (widowed and re-married) abandoned her four children, they went to live with the 69-year-old Alice. John Keats was nine years old at the time. I haven’t found a street number or any other details of Alice’s house.

Edmonton at that time was a village with a population of about 5,000, surrounded by countryside and separate from London. It was praised in a local history of 1819 as having “many advantages … the beauty of the scenery, the variety of the views, and its vicinity to the metropolis, would not be overlooked by those whose rank and fortune enabled them to select a suitable residence”.

(This is an interesting reminder that the Jennings were comparatively well-off, having successfully run the Swan and Hoop Livery Stables for many years. Unfortunately the financial and legal situation for the Keats children started going pear-shaped following their grandparents’ deaths.)

John Keats and his brothers attended school as boarders in the village of Enfield, which was two miles from Edmonton.

In early 1809, Keats’ mother Frances Rawlings returned to live with Alice and the children in the Church Street house. She was seriously ill, however, and died in March 1810. Despite his comparative youth, Keats nursed her devotedly throughout his school holidays.

Thomas Hammond

In autumn 1810, when Keats was almost fifteen, he left school and began training as a surgeon-apothecary. He was taken on as an apprentice by Thomas Hammond, a neighbour in Church Street and the doctor who had attended both John Jennings and Frances Rawlings in their final illnesses.

The apprenticeship included board and lodging, and Keats took his meals in the main house. The surgery was based in a cottage behind the house, though, and Keats slept in the cottage’s attic.

Keats’ grandmother Alice died in December 1814. By this time, his three younger siblings were all based in London (George and Tom at work, and Fanny at school), so Keats no longer had any family near him.

His apprenticeship with Hammond was completed in mid 1815, and from October 1815 Keats was training at Guy’s Hospital in London.

In Between

Charles and Mary Lamb

The siblings and co-authors Charles (1775-1834) and Mary (1764-1847) Lamb also lived in Church Street, from 1833, in a house known at the time as Bay Cottage – and Charles died there in 1834. This is a private property, but there is an Edmonton Heritage Trail green plaque at the gate, and an English Heritage blue plaque on the house itself. The siblings are buried together at All Saints’ Churchyard, just across the road.

Today

Thomas Hammond’s house and cottage at what was 7 Church Street were demolished in the early 1930s. The current buildings date back to that time, and feature a series of shopfronts at street level. The location is now known as “Keats Parade” in honour of the poet.

A plaque is placed at the centre of Keats Parade, above what is currently a real estate agency. It’s difficult to get a good photo, as there’s a ramshackle wooden box on the wall just below it!

The plaque reads:

On this site formerly stood the cottage in which the poet John Keats served his apprenticeship (1811-1815) to Thomas Hammond a surgeon of this parish

The earlier date is slightly incorrect, in that Keats’ apprenticeship began in autumn 1810.

Details

- Address: Keats Parade, Church Street, Edmonton, London N9 9DP

- Tube: Edmonton Green on the London Overground

- Opening hours: The blue plaque can be seen at any time.

Links

- Church Street page on the Lower Edmonton website, which includes a scanned photo of Thomas Hammond’s Georgian-style house

- N9 page on Walking London One Postcode at a Time website

- John Keats blue plaque page on the Open Plaques website

- Edmonton, London page on Wikipedia

Nearby

Garden at Church Street and Winchester Road

Further along Church Street, on a corner where it meets Winchester Road, there is a small garden with a stone bench featuring a quill as its backrest. The paving at the bench’s foot is carved to commemorate the (male) literary connections of the area, Charles Lamb and John Keats.

The paving reads:

Essayist and Poet of Church St. Edmonton

Charles Lamb “Loved his brethren as mankind”

John Keats “Beauty is truth, truth beauty”

Bronze reliefs by George Frampton

A pair of bronze reliefs also commemorate Charles Lamb and John Keats. These were created by sculptor George Frampton in 1898, and were originally displayed in the lobby of the Passmore Edwards Public Library Building on Fore Street.

The library building is now a mosque, however, and the bronze reliefs can instead be found at Community House, 311 Fore Street, Edmonton, London N9 0PZ.

Please note that this community centre is used by a wide range of people, some of them vulnerable, and anyone visiting should treat the staff and other visitors with respect. Also note that you will be required to sign in at the security desk.

Once in, follow the signs to the cafe (which serves darned good cake). Just before you get there you’ll find a junction of hallways, lifts and stairs. The bronze reliefs are on the wall under the staircase to the right.

St Stephen Coleman Street, London

The church of St Stephen Coleman Street is where John Keats’ parents and maternal grandparents, and his younger brother Tom, were buried. There is now nothing left but a blue plaque.

The Keats Connection

It makes for sad reading! Keats lost all his most significant figures from the previous generations in the space of just over ten years, beginning with his father when John Keats was only nine years old. However, St Stephen’s was also associated with a few more positive occasions.

- His grandfather John Jennings was baptised here on 13 October 1730.

- His maternal grandparents John Jennings (age 43 years) and Alice Whalley (age 38 years) married here on 25 February 1774.

- His father Thomas Keats died on 15 April 1804, and was buried at St Stephen’s on 23 April 1804.

- His grandfather John Jennings died less than a year later on 8 March 1805, and was buried at St Stephen’s on 14 March 1805.

- His mother Frances Jennings Keats Rawlings died five years later, and was buried here on 20 March 1810.

- His grandmother Alice Whalley Jennings died four years later, and was buried here on 19 December 1814.

- Finally, his brother Thomas Keats died, and was buried here four years later on 7 December 1818.

The burials were all in the Jennings family vault.

The church itself was destroyed in 1940. I know it sounds a little ghoulish, but I wanted to know what happened to the bodies … and I discovered they were relocated to Brookwood Cemetery in Woking, Surrey. Follow the link for a separate post about that!

Back Then

St Stephen’s was first mentioned in the 13th century.

It became a “Puritan stronghold” for a while in the 17th century. The playwright and contemporary of Shakespeare, Anthony Munday, was buried there in 1633.

The medieval church was destroyed in the Great Fire in 1666. It was re-built by Christopher Wren, with the exterior completed by 1677. Further work on a gallery and burial vault was done in the 1690s. This is the church that the Keats family would have known.

The church was destroyed by incendiary bombing on 29 December 1940, and it was not re-built.

The parish was combined with that of nearby St Margaret Lothbury – which for various reasons accumulated a number of City parishes, and is now officially known as “St Margaret Lothbury and St Stephen Coleman St with St Christopher-le-Stocks, St Bartholomew-by-the-Exchange, St Olave Old Jewry, St Martin Pomeroy, St Mildred Poultry and St Mary Colechurch”.

Today

Modern office buildings now stand on the site, with retail shops and cafes at ground level. A London Corporation plaque commemorates the church. It reads:

Site of the Parish church of St Stephen Coleman street 1452-1940

You can find it nearly opposite the junction of Coleman Street with King’s Arms Yard, outside Black Sheep Coffee.

Details

- Address: 35 Coleman Street, London EC2R 5EH

- Tube: Moorgate, on the Northern line, and the Circle, Hammersmith & City, and Metropolitan lines

- Bank, on the Central, DLR, Northern, and Waterloo & City lines

- Opening hours: The blue plaque can be seen at any time, though the area is probably ghostly quiet on weekends

Links

- St Stephen Coleman Street page on London Remembers website

- St Stephen Coleman Street page on Wikipedia

- St Mary Lothbury website

See also

Bunhill Fields Burial Ground, Islington, London

The Bunhill Fields Burial Ground has two sad connections with Keats. His youngest brother Edward was buried there, having died while still a baby. A little more than a year later, his father Thomas was fatally injured in a riding accident near the cemetery gates.

The Keats Connection

Edward Keats

Edward was the fourth child of Thomas and Frances Keats, born on 28 April 1801. Unfortunately he died at the age of 20 months. I have never seen any details about a cause of death, but I suppose in a time of somewhat higher infant mortality, such things were lamentably not very unusual.

Edward was buried on 9 December 1802 in Bunhill Fields. Relatives of Keats’ maternal grandfather John Jennings had already been buried there, and it is also very near to where the Keats family were living in Craven Street, so it seems a clear choice of graveyard.

The burial register lists Edward as “brought from Craven Street City Road”, and buried in a common grave, at a cost of seven shillings and sixpence. It gives the location of the grave as 44 on the east-west axis, and 35 on the north-south axis. I’ll have to work out if I can visit to pay my respects (many of the graves are fenced off and inaccessible without a guide). I assume there’s no individual marker.

Thomas Keats

The Keats family moved back to the Swan and Hoop in Moorgate in 1802, when Thomas took over the management of the stables and inn on the retirement of John Jennings.

In the early hours of 15 April 1804, Thomas was riding home (south) along City Road when he fell or was thrown from his horse. We are not sure of the details, as it seems there were no witnesses to the accident. A nightwatchman saw his riderless horse heading for home, and found Thomas lying unconscious outside the gates to Bunhill Fields.

Thomas was taken to a nearby surgeon, but his injuries were beyond help. He was then taken home to the Swan and Hoop, where he died that morning, at the age of 31 years.

While the current gates on City Road only date back to 1868, the main entrance was in the same location in Keats’ time. (There used to be another entrance to the northern section of the grounds as well, but that was set back from the road, and only accessible via an alley between buildings. So I think it’s fairly clear that Thomas would have been found outside where the current gates stand.)

Back Then

The name “Bunhill Fields” probably derives from “Bone Hill”. This dates back to 1549, when over a thousand cartloads of human bones were brought from St Paul’s (soon to be demolished) charnel house. The remains were spread over the moor and covered in soil, creating a flat ‘hill’ in the otherwise marshy landscape.

In 1665, Bunhill Fields was enclosed with walls to be used as a burial ground. The Church of England never consecrated the ground, however, and it was open for the interment of anyone who could afford the fees – so it became popular with Nonconformists.

The most well-known people buried here are John Bunyan, Daniel Defoe, and Romantic poet William Blake.

Bunhill Fields is situated between Quaker Gardens on the west – the remnants of a Quaker burial field used from 1661 to 1855 – and Wesley’s Chapel across City Road to the east – a chapel built by John Wesley in 1778, which you can visit along with his house and his tomb.

Once Bunhill Fields became full – after approximately 123,000 burials over the years – the burial ground was closed to further interments from 1853.

Today

The Corporation of London took on responsibility for running the ground in 1867. They began the process of turning the burial ground into a park – with new walls, gates and paths. It was opened to the public in 1869.

There was damage caused by bombing during the Second World War, and Vera Brittain also described Bunhill Fields as being the location of an anti-aircraft gun.

In 1949, following the war, landscape architect Sir Peter Shepheard was engaged to develop Bunhill Fields. His plans were finally implemented in 1964-65. Much of the original graveyard in the southern section was maintained, though fenced off. The more damaged northern section was cleared and turned into a community garden.

Details

- Address: 38 City Road, Islington, London EC1Y 2BG

- Tube: Old Street on the Northern line and National Rail

- Opening hours: Open every day from 8am to 7pm (or dusk, whichever is earlier)

- Guided tours are available on Wednesday lunchtimes during April to October

- Access to enclosed areas is by appointment only, on Tuesday lunchtimes

Links

- Bunhill Fields Burial Ground official site on City of London website

- Bunhill Fields Burial Ground page on the Historic England website

- Bunhill Fields Burial Ground page on Wikipedia