following in the footsteps of John Keats

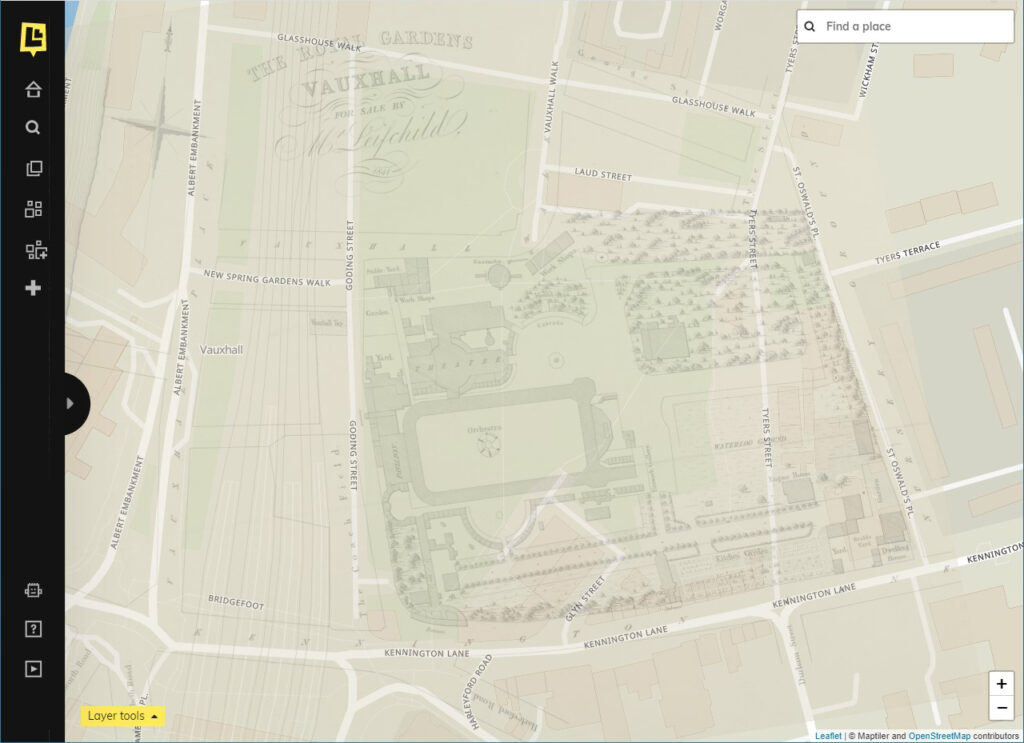

Vauxhall Gardens was an extensive pleasure garden on the south bank of the Thames. It is now a (relatively bare) public park.

Vauxhall Gardens has a long history, with the park dating back to c.1660. It was developed into a pleasure garden during the period 1785-1859, and boasted a risqué reputation. In his biography of Keats, Andrew Motion observes that “the Vauxhall Gardens epitomised the style as well as the tawdriness of Regency London”.

Keats visited the Gardens in August 1814, and spied a beautiful woman – the fairest form he’d ever seen or imagined. He didn’t approach her, but wrote the poem “Fill for me a brimming bowl” describing the torment of being caught between the distractions of his attraction to women and his desire to concentrate on “The Classic page, or Muse’s lore”. Motion describes it thus: “He longs to push women to the side of his mind; he cannot resist pulling them towards the centre.”

Keats is still thinking of this woman in February 1818 when he writes the poem beginning “Time’s sea hath been five years at its slow ebb”, which is dedicated “To a Lady Seen for a Few Moments at Vauxhall”.

Obviously this glimpse of a woman he never knew embodied some ideal sense of beauty for him. We can try to imagine her for ourselves, with “the melting softness of her face” and her “bright eyes”, but we’ll never know what Keats himself saw – or what his memory later conjured.

It’s a tantalising prospect!

The pleasure gardens were permanently closed in 1859, and were built over. However, a slum clearance in the 20th century opened up the area again, and there is now a public park taking up much of the same space as the gardens Keats would have known.

The banner image is “Vauxhall Gardens” (1785) by Thomas Rowlandson, sourced on Wikimedia Commons.

I guess we wouldn’t be here on this site if John Keats himself wasn’t an intriguing person. Fiction authors have found this to be so, as well. Here are some examples – and this post is definitely a work in progress, so I’d love to hear about any more!

What is the truth about the mysterious Dr Cake? Why, at his funeral, is there no name on the brass plate so ostentatiously screwed into his coffin-lid? Andrew Motion, poet laureate, has written a novel about poets and the afterlife.

Where better to start than with Andrew Motion, not only poet laureate but also Keats’ biographer?

However, this book leaves me feeling both satisfied and dissatisfied… but then I wonder if that isn’t the point – or at least one of the many points. This slim novel (142 pages) with its straightforward style is deceptive in that it is crammed full of thought-provoking ideas.

The story begins well-grounded in reality with Motion reflecting on the nature of biography, and specifically what truths the discipline can tell and what truths it leaves out, as well as what is known and what is unknowable about a life. ‘Recently’, Motion declares, ‘I’ve cast around for new ways of doing things.’

Within a couple of paragraphs we are matter-of-factly introduced to Dr William Tabor (1802-1851), who is an invention of Motion’s, though so perfectly grounded in his life and times that one wonders for a while why one hasn’t heard mention of him before in other scholarly works. In turn, Dr Tabor introduces us to Dr John Cake, likewise an invention.

Motion explores the notion that Keats survived a crisis of health in Rome, but let it be thought that he has died, and took the opportunity to reinvent himself. When he eventually returned to England, it was to live and work as Dr Cake, in a village in Essex. His friends and family were left in ignorance to grieve for Keats. When we meet him, some years later, he is finally dying.

A wonderful collection of stories from the much-loved Salley Vickers.

The stories in this long-awaited collection by Salley Vickers all deal with psychological aspects of love: love given and withheld, love craved and lost, love met and disappointed; the differing shades of loves between friends, between parents and children, between children and other adults; love even, in one case, for a pet.

Psychologically acute, sharply written in lucid and often witty prose, these stories, set in Venice, Greece and Rome as well as London and the English countryside, take us into the complex geography of the human heart. Sometimes joyous and humorous, sometimes melancholy and poignant, this collection confirms Salley Vickers’ reputation as one of our most subtle and engaging writers.

Seventeen terrific short stories from one of my favourite authors. I read them all in one day, which probably isn’t wise, but there will be time anon to revisit and retreasure.

Vickers is excellent at deftly setting up the world of a story, and conveying character and emotion. I had a couple of stumbles in the setups and a couple of dissatisfactions with the conclusions, but surely the wonder is that it was only a couple! It might even be churlish to mention them here, but the thing is this: Vickers isn’t perfect, but she’s damned close, and – no matter what – she will always make me think and feel.

This tome is included here as the last (rather short) story, “The Fall of a Sparrow”, focusses on Keats.

On the world called Hyperion, beyond the law of the Hegemony of Man, there waits the creature called the Shrike. There are those who worship it. There are those who fear it. And there are those who have vowed to destroy it. In the Valley of the Time Tombs, where huge, brooding structures move backward through time, the Shrike waits for them all. On the eve of Armageddon, with the entire galaxy at war, seven pilgrims set forth on a final voyage to Hyperion seeking the answers to the unsolved riddles of their lives. Each carries a desperate hope—and a terrible secret. And one may hold the fate of humanity in his hands.

This amazing novel was the rather unexpected path that led me to John Keats! In this futuristic tale, the historical Keats has been cloned and augmented as a ‘cybrid’, and goes on an adventure with a detective named Brawne Lamia. I was intrigued enough to want to know more, about both the man himself and the letters he wrote.

Despite him being a secondary character, Keats really became three-dimensional in my first readings. And Dan Simmons obviously considered him vital enough to name this and the “Endymion” sequels in honour of Keats’ poems.

He was the shameful cause of his sister Elena’s death and he stole state papers from England, yet Adrian Hart is feted by the best of society in Rome, and boldly dubs himself ‘Iago’. Determined to avenge Elena, his unrequited love, Lieutenant Andrew Sullivan asks the advice of poet and Shakespearian John Keats, and his artist friend Severn. Soon Percy and Mary Shelley join them, then Lord Byron and his servant Fletcher. But how can the seven of them work against this man, when they can’t even agree what he is? The atheist Shelley insists that Hart is an ordinary man, while Byron becomes convinced he’s the Devil incarnate, and Keats flirts with the idea that he’s Dionysius…

As death and despair follow in Hart’s wake, Sullivan knows he must do something to stop Hart before even Sullivan himself succumbs – but what…?

And now I will overcome my bashfulness and present my own novel… It’s a Gothic alternate history that asks “What if…?” What if Keats did indeed start recovering his health in Rome? What if he had an adventure instead?

Here is the feisty young man so many of us know and love…

When Michael Crawford discovers his bride brutally murdered in their wedding bed, he is forced to flee not only to prove his innocence but to avoid the deadly embrace of a vampire who has claimed him as her true bridegroom.

It took me a while to finish this one, partly because it’s not my usual fare, and partly because the book takes what feels like a rather problematic view of women.

I wanted to read it because it uses the lives of the Romantic poets Byron, Shelley and Keats as the framework for a tale involving lamias (lamiae?) and vampires. And I have to say that the story and its elements dovetailed very neatly indeed with the poets’ lives as well as their poetry. There was only one convenient shift of an event to a different time (that I caught), but that was understandable for story-related purposes. In fact, sometimes this story fit so well that I exclaimed ‘O ho!’ or had a moment in which I wondered if it wasn’t actually so.

My favourite fellow is Keats, and I thought he was very well written, as were Shelley and Byron. Each man’s loyalties to a tangle of family and friends was acknowledged, though many of these potential extra characters were barely a name on the page. (A very minor detail I found interesting: Powers has Shelley as blond, when the only portrait we have of him shows him with dark brown hair. But I can’t tell you how difficult it was for me to write him with brown hair rather than blond. I blame Julian Sands!) Keats is nobly self-sacrificing in order to prevent harm to others, which I felt was distressingly true to his strong sense of morals.

As for the rest of the novel, perhaps it’s not for me to comment. I found it rather long and needlessly convoluted, but then if this is your sort of thing, perhaps that will instead translate as ‘full and rich’. I have to say I almost gave up on it a couple of times, as it struck me that this ‘man vs lamia’ thing was way too misogynistic if there weren’t balancing factors. Such a point of view might be realistic enough for the characters in their time period, but needs to be handled carefully for the tastes and mores of modern readers. But then at last (past the halfway point) the original character Josephine became rather more interesting, and for better or worse I kept going.

In sum: An ambitious work that succeeds on its own terms. And hurrah for Keats! But based on purely personal taste, I don’t think I’ll be bothering with the sequel (which focuses on the Rosettis).

Wrongly imprisoned, Frederick Whithers is desperate to commit the crime he’s already being punished for: defrauding the bank out of a vast inheritance. He fakes his death to escape, but when he’s seen climbing out of a coffin everyone assumes he’s a vampire; when he shows none of the traditional vampire weaknesses, they decide he must be the Great One, the most powerful vampire in the history of the world.

Half horror and half farce, Frederick’s tale is an ever-growing avalanche of bankers, constables, graverobbers, poets, ghouls, morticians, vampires, vampire hunters, not to mention some very unfortunate rabbits. With a string of allies even more unlikely than his enemies, can Frederick stay alive long enough to claim his (well, somebody’s) money? And if he can’t, which of his innumerable enemies will get to him first?

A silly and amusing tale of fraud, vampires, body-snatching, and other acts of derring-do, set in Bath and London. I read it for the sake of a fictional John Keats, who was actually rather cool, and I loved the tone and content of all he said (though alas we didn’t hear enough from him in the latter parts of the book).

Recommended if you want a bit of nonsensical fun (and don’t mind some rather poor eBook formatting).

Keats visited Winchester from mid August to early October 1819, and famously wrote his ode “To Autumn” there.

John Keats travelled to Winchester from the Isle of Wight with his friend Charles Brown in mid August 1819. Keats was in need of a library while he and Brown were labouring over their play Otho the Great. In a letter to Fanny Brawne, he says, “This Winchester is a fine place; a beautiful Cathedral and many other ancient buildings in the environs.”

On 28 August, Keats writes to his sister saying Winchester “is the pleasantest town I ever was in”, and “the whole town is beautifully wooded”. Unfortunately he had not found a library tolerable enough to satisfy him.

When writing to his publisher, John Taylor, on 5 September, Keats recommends the location: “Since I have been at Winchester I have been improving in health – it is not so confined – and there is on one side of the city a dry chalky down where the air is worth six pence a pint.”

Apart from the play, Keats has been writing “Lamia” and revising “The Eve of St Agnes”, among other poems. He seems to have found some genuine peace and happiness while staying in Winchester.

Unfortunately for such a creative period, Keats is prompted to leave abruptly for London on 10 September 1819, having received a letter from his brother George. Having done what he can about their difficult financial situations, however, Keats returns to Winchester on 15 September.

Keats was in the habit of taking a regular walk down through the Itchen’s water meadows to the Hospital of St Cross, and then back up over the downs. This walk – and in particular the view from St Giles Hill – inspired him to write “To Autumn” on his return to his lodgings on Sunday 19 September.

Charles Brown re-joined Keats in Winchester on 1 October, and they expected to return to London a week later.

I seem to have lost my own photos of Winchester – which is both strange and ironic, as it was perhaps the place I revisited most in England. My first trip was taken in order to follow Keats down along the Itchen to St Cross (though I came back the same way rather than over the hills). I deliberately went in autumn, of course! But I returned time and again, in all seasons.

The building in which Keats and Brown lodged has been demolished, but is thought to have been very near where the Visitor Information Centre is, on the ground floor of the Guildhall.

My other writerly hero is Jane Austen, who now rests in Winchester Cathedral. Indeed, the “Keats Walk” takes you along College Street past the house in which she lived her last months.

As Keats noted, the Itchen is indeed “a most beautiful clear river” – though I understand there was a serious effort taken in modern times to clean it up. The effort was perfectly successful! The water in the little stream one walks beside is as pure and clear as crystal.

I particularly fell in love with the Hospital of St Cross and Almshouse of Noble Poverty (to give it its full name). The historical buildings preserved here are remarkable, and the Norman/Gothic-style church is both beautifully sturdy and elegant.

Apart from all these delights, Winchester boasts remnants of the Saxons and the Romans, a ruined castle, a medieval hall (with a 13th century mock-up of Arthur’s Round Table), the 15th century City Cross, surviving portions of the city walls and gates, a Gothic-revival style Guildhall, and more. With all that and its beautiful setting in the Hampshire countryside, to me it feels as if it’s a quintessential piece of England.

The banner image was taken by Celuici in August 2018, and was sourced on Wikimedia Commons.

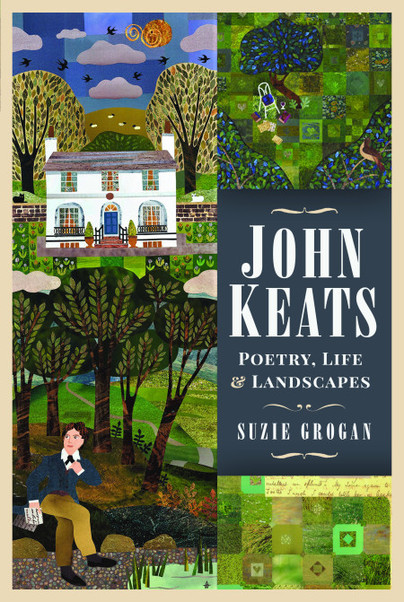

John Keats as a person (and as a poet, and a letter-writer) is easy to love; his contemporaries found it so, and readers have continued to fall for him ever since. Suzie Grogan certainly did, and I did, too.

In her Introduction, Grogan quotes Keats as saying, “We read fine things but never feel them to the full until we have gone the same steps as the Author.” Keats was talking metaphorically, about empathy and life experience – but maybe he would have understood we Locations Geeks who enjoy tracking down the places he knew, and literally following in his footsteps. Some of those places and their treasures have been carefully preserved, while others have been significantly changed or even destroyed – but they all offer experiences and perceptions that enhance even the driest sentence in a biography and help bring it to three-dimensional life.

The first (and most substantial) part of this book is a lively biography of Keats, of the places he visited and the writings (both poems and letters) they inspired. Along the way we are given glimpses of Grogan’s own developing understanding of him and his work, from her teenage years, through her own serious health challenges, and into maturity. Chapters are organised mainly by location and then by chronology, so that we are not following Keats through time so much as through place; a deft way to handle his many to-ings and fro-ings.

The whole is lightly written and easy to read, but full of insight, and it conveys a great sense of Keats the man. It even begins with a consideration of the portraits and written descriptions of him by his friends, so that we might see him in our mind’s eye while we accompany him on his travels. For anyone new to Keats, I suggest this is an excellent place to start. There are weightier and more scholarly biographies, but Grogan admirably shows why it’s worth making the effort to read them as well.

The second part of the book provides a few paragraphs on each of those in the Keats Circle who’ve been mentioned during the earlier parts of the book. The focus is still firmly on Keats, however, and on these people’s influence on his life and work and on his later fame and reputation. This is followed by a chronology of key dates, copies of some key poems, and a bibliography.

Highly recommended to those new to John Keats, and to those who already consider themselves a “Friend of Keats”.

Note: I received a PDF ARC from the publisher, and this Keats Locations website is mentioned kindly in the Acknowledgements. But I was always going to be an Ideal Reader for this work, so you may take any gushing as a genuine response. (And I’ve already pre-ordered a hardback copy for myself.)

Westminster Abbey is a significant and central part of British history, and its Poets’ Corner includes a memorial to Keats.

A monastic community was established in this location in c.960, with a stone church named St Peter’s Abbey being built by King Edward and completed in c.1065. Edward was buried there not long afterwards in 1066, and on his canonisation the site became a place of pilgrimage. St Peter’s and the adjacent Palace of Westminster are depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry.

The current church dates back to the 13th century and King Henry III.

Many of Britain’s royals are buried in the Abbey. It has been used for coronations since 1066, and also for many royal weddings.

Poets’ Corner began haphazardly. Chaucer was buried elsewhere in the Abbey in 1400, due to his place in the royal household rather than his reputation as a poet. In 1556, fellow poet Nicholas Brigham installed a marble tomb for Chaucer in the Abbey’s south transept, and had his bones moved there. Edmund Spenser was interred near Chaucer, as he wanted, in 1598.

From there, burials and memorials accumulated. Over 100 poets, dramatists and prose writers are now buried there, with memorials to many others who are interred elsewhere. The name “Poets’ Corner” is first documented in 1733.

The Keats-Shelley Association paid for memorials for both poets, which were installed on the Shakespeare wall, and unveiled in 1954. The tablets are simple and elegant, with a carved marble “swag” of flowers and foliage uniting them. The inscription reads:

Keats 1795-1821

The Abbey and Poets Corner are well worth visiting. The latter includes memorials to William Shakespeare and George Frederic Handel, as well as Keats’ contemporaries William Blake, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Robert Southey, Lord Byron, Jane Austen, John Clare, and Sir Walter Scott.

Keats himself predicted – or at least hoped and trusted – “I think I shall be among the English Poets after my death.”

A fascinating look into the physical and social context of Winchester, amidst which Keats was inspired to write his ode ‘To Autumn’.

This article by Richard Marggraf Turley, Jayne Elizabeth Archer, and Howard Thomas appeared in the Oxford University’s Review of English Studies (Vol 63, Issue 262, November 2012). It has been made available for free in honour of the bicentenary of Keats’ death.

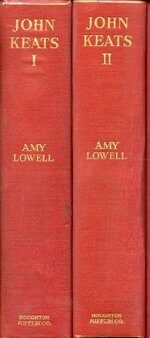

This was a brilliant biography, and I really enjoyed reading it. For Keats lovers, I would recommend it as a great companion to Andrew Motion’s Keats and Nicholas Roe’s John Keats: A New Life. It is wonderful to get the perspective of a woman on Keats as a person, and on Fanny Brawne, too. Amy Lowell was also a poet, and considers Keats’ poetry with a no-nonsense poet’s eye. The other aspect of this biography that stands out is that it was written a hundred years ago, and has a strong authorial presence – akin to that in 19thC novels – rather than the reticent, self-effacing authorial voice of modern biographies.

There are a few instances where Lowell reaches an incorrect conclusion, or where she didn’t have access to papers or knowledge discovered since her time. However, she always makes clear her line of reasoning, so the well-read Keatsian won’t find themselves astray.

There is a great deal of analysis of Keats’ poetry, which won’t suit every reader, but it is usefully integrated with his personal biography, and I happily read every word. Lowell is also great in her consideration of Keats’ almost religious approach to beauty, love and truth.

One of the things Lowell brings to the table is a clear love for John Keats – which is how many or even most people respond to him – and a personable manner in which the reader feels we’re sitting down with Lowell for a delightful long afternoon to talk together about one of our favourite people. Not that she lets her affection blind her, for she is always honest and open about those times in which Keats behaved or wrote in ways that were less than ideal.

I think it took this woman biographer to clearly see the problem with Keats’ letters to Fanny Brawne: his selfishness. Other people have written about his jealousies and insecurities, which are clear in the letters and are understandable (if not really forgivable) in the circumstances – but they are not the crux of the problem. Lowell gets right to the heart of it. As a result of this and of other very reasonable considerations, Lowell is utterly fair to Fanny Brawne as a patient, intelligent and loyal woman – an excellent match for Keats, even if his friends at the time didn’t see it or didn’t want to see it. One wonders why the controversy about Brawne and her suitability still lingers on!

Lowell is similarly clear-sighted and fair about Keats’ various friends and relations. Some of this was delightfully refreshing to read.

Highly recommended for all Keatsians. It’s out of print, alas, but worth tracking down!

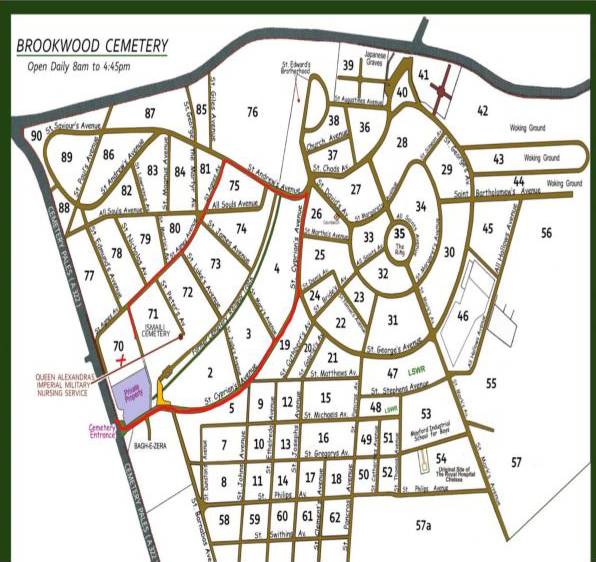

Some of John Keats’ most significant family members were re-buried in Brookwood Cemetery in 1959-1961. Keats wouldn’t have known the cemetery at all, as it only dates back to 1854, but I am sure he would want us to honour it as a Keats Location.

John Keats lost a number of significant family members over the years 1804-1818: his parents, his maternal grandparents, and his younger brother Tom. They were all buried at the St Stephen Coleman Street church in London.

The church was destroyed by enemy bombing in World War II, on 29 December 1940, and it was not re-built. When the land was eventually sold (to the Swiss Bank Corporation), the new owners were required to exhume and move the remains – a procedure to be “carried out with all due reverence”.

The exhumation and reburial was undertaken by the London Necropolis Co Ltd, starting in July 1959, and completed by September 1961. The remains were reburied at Brookwood Cemetery in Woking, Surrey.

Brookwood Cemetery, also known as London Necropolis, was opened in 1854. It was served by the London Necropolis Railway, with a dedicated railway station for departure in Waterloo, London. (You can still visit the Cemetery care of Brookwood station today.) The Cemetery is a huge site, covering 500 acres – the largest cemetery in the world at the time, and still the largest in the UK – and was intended to serve as London’s first choice of burial site for centuries to come.

It is no coincidence that burials at St Stephen Coleman Street were discontinued in 1853, at the time Brookwood Cemetery was being planned and developed. London was dealing with a “burial crisis”, as the growing population and consequent increasing need for burials were overwhelming the resources of churches and cemeteries within the city.

While Brookwood Cemetery never really dealt with as many new burials as hoped, the site was used for mass reburials. The large-scale engineering works in London taking place in the mid-1800s – the railways, the sewer system, the Underground, and so on – necessitated the relocation of a number of burial grounds. The first such relocation took place in 1862, when the development of the Charing Cross railway station and associated railway lines prompted the removal of the Cure’s College burial ground in Southwark; this involved almost 8000 bodies.

Eventually, when it came time to relocate the remains belonging to St Stephen Coleman Street in the mid-1900s, I assume that Brookwood Cemetery was the obvious (perhaps even the only) choice.

It was requested that the Rural Dean read a service over the re-interred remains.

I discovered this information about the fate of the St Stephen Coleman Street remains care of a visit to the London Metropolitan Archives. I then requested a Grave Search at Brookwood Cemetery. My thanks are due to staff at both these locations for their friendly assistance!

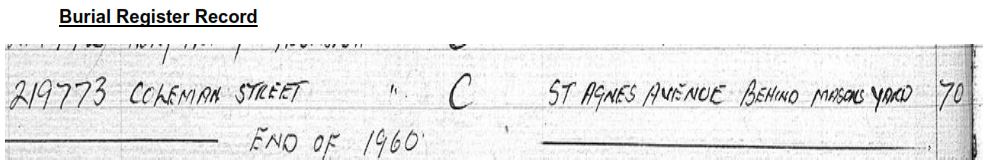

It took some searching, but the Senior Administrator at the Cemetery was able to confirm the reburial and its location:

I can confirm St. Stephen Coleman Street reburials are buried at Brookwood Cemetery; the location of the reburials is on the South side on Plot 70 St Agnes Avenue behind what was known as the old Masonry Yard (now known as Beard Constructions). Behind and beyond the Masonry works is one of several areas in this section of the cemetery used for reburial of human remains from churches and churchyards in London.

Correspondence received 30 July 2019

The specific grave number is 219773.

The Senior Administrator goes on to say that there would not have been any records of the deceased individuals, nor would a marker have been placed on the plot at the time. If there has been a memorial raised since then, it is not currently visible due to the area being overgrown. (The maintenance team will be clearing it in due course.)

It does seem a bit sad that these people who meant so very much to Keats are now buried “en masse” with no marker. The specific location makes some amends, with the address recalling his poem The Eve of St Agnes, and we can certainly consider them at rest in this lovely park-like setting. (Personally, I wouldn’t mind a whole swathe of ferns growing over me.)

Looking through the records kept at the London Metropolitan Archives, I found that there was some belated recognition that Keats’ family were involved in the relocation of remains. The London Archdiocese Fund was required to give notice of the re-interment so that any descendants could make suitable / alternate arrangements. There is a copy of a memorandum which refers to “a young lady” of “the Keats-Shelley Society” approaching them with a query about “a family member” of Keats. The general tone is rather unsympathetic, and she was told she was too late – though it seems she was less than a month past the deadline. My instinctive thought was that surely some efforts could have been made, but the note ends with the remark that perhaps it’s just as well she was too late, as what could be done? {virtual shrug} It hardly needs saying that this attitude rather undermines the “all due reverence” requirement.

There are later written queries from a London chap, dated 1969 and 1970, asking what would have become of the Keats family remains. While his query was referred to someone whose name I recognised from earlier related records (and who would have known the answer), there was no copy of any information being sent to the enquirer.

Which leaves the question open as to what, if anything, might be done now to honour John Keats’ family. They were good people, but not famous in their own right. Is it enough to know where they are, and to go pay our respects if we feel so inclined? On one hand, I am sure he would care deeply about them not being lost entirely to us. On the other, perhaps even he would consider a memorial of some kind to involve money better spent on the living. And after all, perhaps it is more a matter to be decided by the descendants of John Keats’ brother George and sister Frances.

So, for now … Rest in Peace: John Jennings; Alice Jennings (nee Whalley); Thomas Keats (father); Frances Rawlings (formerly Keats, nee Jennings); and Thomas Keats (brother).

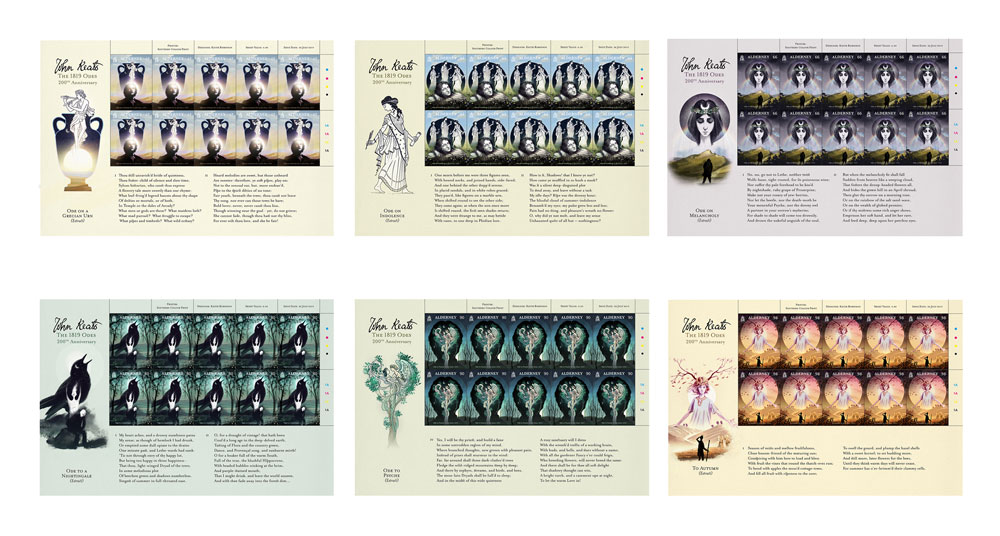

We shall have to consider Alderney, one of the Channel Islands, an honorary Keats Location! On 24 July 2019, the Guernsey Post released a set of six postage stamps commemorating the six lyric odes Keats wrote in 1819.

There is nothing (that I’m aware of) to indicate that Keats ever visited or had any connection with Alderney. I wondered if his ship, the Maria Crowther, might have put in there during his last voyage to Naples. However, the ship stayed close to the English coast due to challenging weather, and only started sailing south after Portland Harbour. The voyage is then described as passing the tip of Brittany before reaching the Bay of Biscay, which indicates that they passed by the Channel Islands at some distance.

Anyway! Why do any of us need a “reason” to commemorate our beloved English poet? Keats is probably best known by the mainstream population for these six odes, written in what biographer Robert Gittings called his “Living Year”, when he was 23 years old. This “Alderney issue” was designed by Keith Robinson, and features lovely illustrations that include Keats himself along with imagery drawn from the poems.

I have copied below the images from the Guernsey Post website, without permission but with the greatest respect and gratitude. Follow the link below the images to visit the site itself!