Brilliant. Just brilliant. The biography by Andrew Motion has been my Keatsian bible for many many years now, and while I reluctantly began thinking it was probably about time for an update, I also dreaded the prospect. I really love and admire John Keats, and Motion was a big part of me getting to know him; I didn’t want to lose my (always inadequate, always conditional) grasp on who Keats really was.

Of course I needn’t have feared, and any courage needed certainly paid off. This is a great book, a truly great book, and I think it works perfectly as an addition to (or a complement of) Motion’s work as well as the work of others.

My take on Motion’s Keats is that he was both a poet and a medical man, a healer of both bodies and souls. Roe’s Keats is a poet (full stop), and any return to his training or work as an apothecary would have been a turning away from his true self. Which is right? I don’t know, but it’s very interesting to consider the question in such detail.

Roe’s strengths are in Keats’ early years – his childhood and then right through to his time at Guy’s Hospital – and in Keats’ poetry – which is given terrific context in the poet’s life and times, and thus enhanced meaning. Roe is also very knowledgeable about Keats’ relationship with Leigh Hunt – which is no surprise as Roe is also Hunt’s biographer.

Roe very interestingly touches on the idea that Keats was very conscious of passing time, and in particular the things that mark it: the anniversary of his father’s death, the new or half or full moon, the date he announced his decision to be a poet to his friends, and so on. Keats even contrived to die late on the day of the ancient Roman festival Terminalia, which honoured the god of boundaries. I’m not entirely sure how seriously we are to take this, but there’s no denying that Keats’ work often deals in liminalities, and Roe certainly conjured a number of relevant happenings and images along the way to give credence to this – especially the late-night farewells between young Keats and his teacher Charles Cowden Clarke on the bridge between their homes.

There were certain areas of Keats’ life that I felt weren’t given much space on the page. Especially, but not only, Keats’ love and fiancee Fanny Brawne. I’m not sure whether this is due to Roe deciding that such things had already been well covered (and I certainly think Motion does justice to Brawne). Or that 400 pages is enough, and something had to be dealt with truly though briefly. I’m hesitant to think that Roe didn’t think Brawne important… I mean, OK we’re not all interested in a man’s love life, but she was important to Keats the man and Keats the poet – and Roe does give her her due, even if a little too succinctly – so let’s go back to my initial thought of such things being covered well elsewhere.

Which takes me back further to the notion that this book is a great addition and complement to the existing work on Keats. And leads me on to the notion that perhaps, even for a life this short, there can never be a definitive ‘Life’. Read this, and read Motion, and read as much of the rest as you like. Keats himself will repay you well.

Links

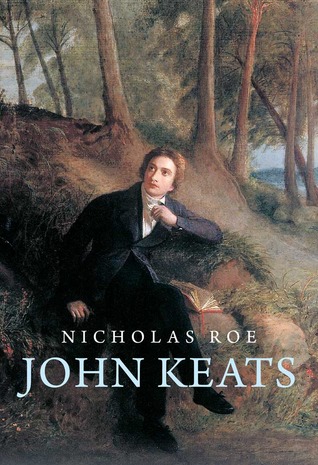

- “John Keats: A New Life” by Nicholas Roe page on Goodreads